Written By: Ran Levi

A surprising discovery in the field of linguistics, made by a William Jones, a British judge in India, uncovered the existence of the Indo-European language: an ancient language, the ancestor of an amazing variety of modern languages – from English and French to the Persian Farsi and Indian Sanskrit. The speakers of this language didn’t leave any written evidence behind, but researchers were able to reconstruct it never the less. How? With the help of Jacob Grimm, of the Grim Brothers.

A surprising discovery in the field of linguistics, made by a William Jones, a British judge in India, uncovered the existence of the Indo-European language: an ancient language, the ancestor of an amazing variety of modern languages – from English and French to the Persian Farsi and Indian Sanskrit. The speakers of this language didn’t leave any written evidence behind, but researchers were able to reconstruct it never the less. How? With the help of Jacob Grimm, of the Grim Brothers.

This article is a transcript of a podcast. Listen to the podcast:

Download Part I (mp3)

Download Part II (mp3)

Subscribe: iTunes | Android App | RSS link | Facebook | Twitter

Explore episodes in other categories:

Astronomy & Space | Biology & Genetics | History | Information Technology | Medicine & Physiology | Physics | Technology

Part I: Discovery of The Indo-European Language

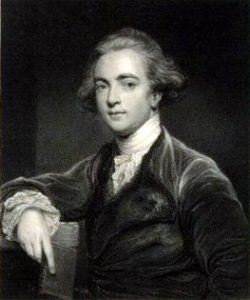

Sir William Jones

In 1783 a British lawyer named William Jones arrived in India. He had the honor of being welcomed by the local British governor himself, even though there were many other politicians and officials from Britain already in India.

Jones’ father passed away when William was only three-years-old. The father, a famous mathematician, left a small inheritance – just enough to give young William a proper education. Several years later the boy was recognized for having a unique and rare talent for languages: at age ten he could already speak fluent Arabic, French, Italian, and Hebrew.

by the time Jones was twenty-years-old he spoke twenty-eight languages. He was particularly attracted to eastern cultures – Mesopotamia and south East Asia – which were considered at the time to be unusual and exotic. His expertise in languages in addition to his familiarity with those cultures got him a reputation for being an expert on what was then called “The Orient.”

William Jones’ talent in languages was known all over Europe. When he was only twenty-two, the king of Denmark requested his help with translating a book from Farsi to French, and books that Jones wrote on eastern languages were considered a breakthrough in the field of linguistics.

William Jones was a rock star of academics in the 18th century: he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society – one of the most prestigious academic institutions in the world – and was even knighted. But prestige doesn’t pay the bills. In order to sustain himself, Jones had to study law and work as a lawyer. Money was also what eventually brought him to India. In 1783 Jones heard of a vacant position as a Supreme Court judge in Calcutta. In Great Britain, India was thought of as a gold mine since trading opium, spices, and gold made many British people very wealthy. Jones pulled some strings and won the position.

A Radical Liberal

The socio-political status of the late eighteen hundreds in India was complicated. The British government ruled over a huge population, and they had a continuous fear of restlessness and rebellion. The local British governor of Bengal had a very liberal approach: he believed that in order to gain the trust of the local population, the British governance should rely on local laws and traditions – instead of forcing foreign European laws on the people of India.

William Jones identified with this approach, and in fact – he was known among the political circles as a radical liberal, due to his support of the colonies in America who were opposing the British Government. Respect and appreciation of other cultures were deeply rooted in his character.

But when Jones took the seat in the Calcutta Supreme Court, he found a flaw in the liberal approach. The Hindu laws and traditions were based on ancient books written in Sanskrit – an ancient Indian language. Sanskrit was familiar to scholars, but just like Latin – some studied it and conversed in it, while never speaking it as a mother tongue.

The British judges in India didn’t speak Sanskrit, therefore they had to rely almost blindly on local scholars known as “Pandits” who translated the ancient scripts. Jones feared the blind dependency on Pandits since it encouraged bribery and corruption which were hard to fight. So, Jones decided to take up the gauntlet himself: he would study Sanskrit and translate the scripts to English by himself.

Learning Sanskrit

It wasn’t easy. The local Pandits weren’t thrilled to give up their natural monopoly over the law, or in other words – to give up their source of power – and teach this British judge the secrets of the ancient language. It took a lot of effort for Jones to find a Pandit who was willing to teach him Sanskrit. According to one version of the story, even this Pandit wasn’t thrilled to expose sacred traditions to the impure, cow-eating judge, so he made strict demands: Jones must study in a room that was ritually purified and on an empty stomach – except for a few cups of tea here and there. Jones agreed to all these demands. It’s hard to tell whether this story is true or an exaggeration, but at the very least it shows William Jones’ determination to study Sanskrit.

Within just one year Jones has learned Sanskrit. He felt so confident in his abilities that he ruled in a rare case where two Pandits couldn’t agree over an interpretation of some old text. Jones studied the source, translated it to English, and ruled a ruling that was considered a precedent.

An Unexpected Phenomenon

With his new knowledge of the ancient Indian language, Jones noticed a surprising and unexpected phenomenon. Quite a few words in Sanskrit resembled parallel words in Latin, Farsi, Greek, and English. For example, the word for “mother” in Sanskrit is “matar”, which is very close to the Farsi word “madar,” the Latin word “mater,” and the English – “mother.” The term “king of the Gods” in Sanskrit is “dyaus pitar,” which literally translates to “sky father”: pitar being “father.” In ancient Greek, the king of the Gods was called “Zeu-pater”, later known as “Zeus.” Here too, pater is “father.” The Latin king of the Gods is “Iu-peter”, or in its modern version – Jupiter. And again, peter is “father.”

Jones realized that the resemblance between the Sanskrit “pitar”, the Greek “pater,” and the Latin “peter,” couldn’t have been coincidental. This fact became clearer, as Jones found more resembling words of different languages.

Now, This sort of resemblance is common within European languages, and the Europeans had been aware of it for quite some time. French, Spanish and Italian are very close to each other both in grammar and vocabulary. For example, “woman” in Spanish is “mujer,” in Italian it is “moglie,” and in old French, it is “moillier.” The reason for this resemblance is that these three languages are descendants of Latin, the official language of the Roman Empire. That is why they are called “the Romance languages.” After the Empire collapsed around the fifth century AD, the Latin local dialects became different languages, while a basic resemblance was perpetuated over generations.

Another example is the resemblance between the Germanic languages – English and German, for instance – and the Romance languages. The odd thing here, however, is that the Germanic languages developed separately from Latin. The common explanation for this resemblance has to do with the constant friction between the different cultures in the continent: the Germanic peoples traded, fought, conquered their neighbors and were conquered by them – allowing many foreign words to enter their language.

The Indo-European Language

Yet the resemblance Jones exposed couldn’t be explained by that friction since the Indian culture and the European one were very distant from each other, and hardly ever had any real contact. So the only other viable explanation for the resemblance was a common source – and that was the assumption that Jones wrote about in this article from 1788:

“The Sanskrit language, whether by its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure, more perfect than Greek, more copious than Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a strong affinity, both in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar – than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed that no philologer could explain them all without believing them to have sprung from the same common source.”

In other words, in the same way Latin split to several languages, perhaps there was a proto-language that Sanskrit, Farsi, Greek, and Latin had come from. The name given to the hypothetical language that Jones exposed was “Proto-Indo-European”, or just “Indo-European” – a name that denotes the connection between Sanskrit and the European languages.

Jones wasn’t the only scholar who identified the similarities between Sanskrit and Latin – there were a few other linguists who assumed the same, several decades prior to Jones. But it was Joneses’ reputation as an expert of “The Orient” that validated the assumption and encouraged others to continue his work.

His ideas really fired up the minds of European linguists! If Jones was right, and this proto-language was spoken, then it must be extremely ancient since the cultures of the Persians and the Indians had separated thousands of years ago. Which brings us to the question we asked at the beginning: how can we research the Indo-European language? If it is so old, then it must have existed before writing was invented, and therefore we have no way to study or research it! no stories, no folk songs, no legal documents, or even recipes. a language that once existed, and then vanished forever.

Or did it?…

The Holy Roman Empire

I want to introduce you to a very special man. This is Kevin Stroud. He is a lawyer with a great passion for linguistics and languages. I met Kevin through his “History of English Podcast” which chronicles the development of English from its most ancient roots. For a language nerd such as myself, Stroud’s podcast is amazing: a combination of linguistics and history.

“My name is Kevin Stroud, I’m the host of the History of the English Language podcast, which I started back in 2012. So many history podcasts focus on military histories or social histories – but very few, none that I know of, focus on linguistics history. So I always thought it would be interesting to tell the story of the English language, but tell it in the context of the over-arching history of the English-speaking people, and combine the linguistic history with the social and military and put it all together. That’s the concept of the podcast.”

As Stroud will tell us in a moment, the first breakthrough of the Indo-European studies wasn’t related to science or linguistics. And the person responsible for it is none other than Napoleon!

Ok, let’s set the stage: the Holy Roman Empire was an odd creature in the European political map. It was founded in the ninth century AD, ruled over what we consider today to be Germany and Austria, and therefore included the majority of German speakers in Europe. But the Holy Roman Empire wasn’t a nation-state the way we define it nowadays. Although the Emperor had authorities, they were limited; The true rulers were numerous kings, princes and counts who governed roughly 300 small kingdoms, duchies, and counties who made up the Holy Roman Empire.

In the early 19th century Napoleon conquered vast German territories and annexed “Rhineland” to France. The French occupation sparked a nationalistic flame among the Germans, who understood that if the Germans wanted to become a real power in Europe, they should unite and join together. As long as the Germans were scattered around in all those small duchies, Germany would not be able to face the other powers surrounding it.

“William Jones did his work in the late 1700’s, but then you get into the 1800’s, and within Germany, there’s this awaking sense of nationalism. Germany has just come off a period where it was occupied by France in the Napoleonic period, and now France has been pushed out and we’re beginning [to see] a process where city-states and principalities are starting to unite. That had not happened yet – but the process was beginning. Among all of the various peoples within the area we now know as Germany, one thing they had in common was a language. They all shared the same Germanic language.

There started to be […] a strong interest in the Germanic language family, that thing that united them together. One of the most important figures in that process is a name that many people will recognize: it was Jacob Grimm, one of the famous Brothers Grimm.”

Jacob Grimm

Jacob Ludwig Carl Grimm was born in 1785 in the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, one of the smallest states in the Holy Roman Empire. Jacob and his younger brother Wilhelm were deeply affected by the rising patriotic feelings among the Germans. When they became scholars, they researched the history and culture of Germany and tried to figure out what elements joined the history of all Germans; the history blurred any divisions, Like, folklore songs and stories. Together, Jacob and Wilhelm gathered and adapted old folk songs and tales, among them “the princess and the frog,” “sleeping beauty,” and “Hansel and Gretel.” Their book “Grimm’s Fairy Tales” from 1812 was a great success and created a reputation for the brothers all around Europe.

As Stroud pointed out, Jacob Grimm’s interest in languages also stemmed from these national tendencies. As a part of his literary work, he researched the roots of different Germanic languages – German, English, Swedish, Icelandic, and other Scandinavian languages – in order to identify and emphasize the uniting characteristics within that family of languages.

He was focused on researching the nature of connections between words in different languages. Let me give you an example: Let’s say I come home after a long work day, only to find the hallway walls covered with scribbles and paintings which can only be cleaned with a bulldozer. Let’s also assume that I see Marom, my youngest son, sitting on the sofa with color stains covering his hands. I would love to tell you that this is a fictional example, but I am not that creative. Now, the question we must ask is: what is the connection between the boy and the wall? How can I be sure that the child is the one who earlier drew on the wall and is now sitting innocently on the sofa? Perhaps the marker colors on his hands are a result of an art project at kindergarten?

Taking this analogy back to the world of languages and words, a resemblance between two words – for example, the English word “father,” and the Greek word “pater” – can be explained in numerous ways. For instance, it is possible that English borrowed the word from Greek, just as many languages around the world borrowed the word “telephone” or “fax” from English. Or, the two words could have had a common source in a third language, a language that existed before them. A third possibility is that the resemblance is purely random. So how can we identify the nature of the connection?

When it comes to my painted hallway, the answer is pretty clear since I know the actors of that play. But in the case of words, finding connections isn’t as simple.

“Jacob Grimm, what he did was he took not just dozens or hundreds – but thousands of words within the Germanic languages, and then he compared them to words meaning the same thing in other languages like Latin and Greek. He concluded that there were certain patterns emerging here.”

Sound Shifts

Grimm analyzed numerous words in different languages, searching for patterns and repetitive structures. Let’s look at the letters “P” and “F”. Grimm noticed that within the Germanic languages the sound “p” systematically shifted to the sound “f”. For example, did you know that the words “pen” and “feather” come from the same Latin word? they sound different until you identify the sound shifts. The original Latin word was “penna”, meaning feather. It made its way to English through French – which is, as you recall, a daughter language of Latin – and from “penna” the word became “pen”. And since in the past people used to dip feathers in ink in order to write, the meaning of the word shifted to describe stationary. But the same word – penna – survived in German as well, not before the sound “p” shifted to “f”, which then rolled to become the English word feather. In other words, the same original Latin word entered English through two different routes. The Germanic route included a sound shift from “p” to “f.” The same shift can be found in many other Latin words that passed through the German language. For example:

Foot – Ped (as in Pedometer)

Fire – Pyre (as in Pyromaniac)

Why did this shift happen? It’s hard to say for sure, of course: it happened so long ago, as part of the natural development of a language – but it probably had to do with the resemblance of the sounds. When we pronounce the name of the letters, “p” and ‘’f” – they sound quite different, but once you pronounce the sounds they make “p, f”, you can notice how close they actually are. In the sound of “p”, the air is blocked in the lips, while in the “f” sound, the air is completely free – but the sound is actually similar.

In fact, in addition to the p-f sound shift, Jacob Grimm identified eight more shifts. For example, a shift from “d” to “t.” The Latin word for a tooth is “dentis” – the source of words like Dentist and Dental. After the German sound shift from “d” to “t’” we get the word “tooth,” with the same exact meaning. By the way, this sound shift is still taking place nowadays: in modern American English a word like “bitter” is pronounced as “bidder.”

And here is another example: in Latin, the word “cord” means heart. From “cord” we get the Spanish word “Corazon,” and the English terms cardiac and cardiology. Grimm identified a sound shift from the letter “C” to “H” – which is how we got the word “heart” with the same original meaning. And one last example: the Latin word for head is “caput,” from which we get words like “captain” (head of soldiers), the French word “chef” (head of the kitchen), and many others. Due to the sound shift from “c” to “h” – we got the word “head”. Kapish?

An Important Conclusion

The phenomenon of sound shifting was identified before Jacob Grimm – but Grimm was the first to recognize it as a real pattern, instead of a collection of random and coincidental examples. And now the linguistic sound shift is named after him: Grimm’s Law. The shift didn’t just happen anywhere, it was dependent on other factors, likes the location of the letter “p” in a word. But once they know these factors, linguists were able to reliably recognize them and conditions it took for a sound shift to occur.

Identifying the sound shifts brought Grimm to an important conclusion:

“And what he realized is that these words all came from the same source, but the sound had shifted. He put two and two together, and said – at some point in the distant past, the early Germanic speakers, back when it was one common language, they had a sound shift.”

In other words, Grimm realized that the sound shifts are responsible for the differences between existing words in Sanskrit, Farsi, Latin, Greek, and all other descendant languages of the Indo-European that Jones exposed. Grimm concluded that at some point within the distant, foggy past, the Indo-European speakers split into several ethnic groups who settled in different geographical areas. One of those groups, for example, started pronouncing the sound “p” as an “f” – and this was the seed from which the Germanic languages grow. Another group, from which Latin developed – kept the sound “p.”

Reverse-Engineering Words

What is the significance of Grimm’s Law? Well, let’s return to the crime analogy. Imagine that you are detectives trying to solve a case of a car theft. The original car had been taken apart, and no longer exists in its original form. Now you are looking at three different cars, and you suspect that the thieves dismantled pieces from the stolen car and installed them in the cars you are seeing now. So how do you know what the original car looked like? Well, if you can identify which parts were replaced, you can reconstruct the original vehicle. For example, if you know that in one car the doors were replaced, in the other – the tires, and in the third – the headlights, then you know what the doors, the tires, and the headlights of the original car looked like…

“This is where other linguists took Grimm’s work and applied it in reverse.”

Grimm’s Law allows us to reverse-engineer words. Take existing words in different languages, descendants of one common word of the Indo-European language, and apply Grimm’s Law on them – in reverse: restore “f” to “p”, “t” to “d”, “h” to “c” – and reveal the original word.

“Of course, there’s no way to know if that’s how the words sounded like, but – beyond the work that Grimm did, other linguists did the same work within the other language families. So, within Latin, they were able to identify specific sound changes there as well.

So what they were able to do was to take words within Latin and Greek and other language families and they were able to reverse engineer those words as well, applying the sound change rules in reverse. And if you take the sound changes within the Germanic languages, and do the same thing in Latin and Greek – what they discovered was that in many instances they ended up with the same word. The word was virtually identical in all those different languages.”

Discovering the Indo-European Language

Since the Indo-European language became many different languages, from Farsi and Sanskrit to Latin and German, linguists could reverse-engineer many words sharing the same meaning. If they ended up with the same word after reversing the sound shift they determined that the word originated from the Indo-European language. For example, they took the English word “sister”, The Latin word “soror,” (which brought us the word ‘sorority’) the Sanskrit word “svasar,” and the Farsi word “xanhar” – they all have the same meaning – sister. Then they reversed the sound shifts, and all the words became the same Indo-European word: “swesor.”

This way linguists were able to do something that at first sight seemed impossible – they reconstructed words of a language that disappeared more than four thousand years ago, a language that was never even brought to scribe. Here are a few examples:

oxen – uks-en

mother – mater

apple – abel

seven – septm

one – oinos

More than a thousand words were discovered this way! This amazing achievement – reconstructing an ancient language from existing words – is mind-blowing, and becomes even more impressive when we understand the repercussions of the linguistic work.

Part II – Who Were The Indo-Europeans?

Here’s a summary of what we have discovered so far. William Jones was an English judge posted in Colonial India in the eighteenth century. He had a reputation as a linguistic prodigy–he spoke many languages–and while in India he noticed a remarkable resemblance between ancient Sanskrit and European Latin. This discovery led him to believe that the source of Farsi, Sanskrit, English, French, and, well– almost all the European languages, was one common ancient language called “Proto-Indo-European”, or just “Indo-European.” About half of the world’s population today speaks a language that is descended from Indo-European.

“Just about every European language. It’s easier to say which European languages are not part of that family. From Russian to French to English and Dutch, it’s all part of that family. There are a few exceptions: The Basque language of northern Spain, the language of Hungary is not considered to be Indo-European, and a few languages in northern Europe. Also the many languages of northern and central India. The languages of Iran, Afghanistan – those are descended from ancient Persian. … All of those languages came from the same source.”

In Germany, the French occupation of the late eighteenth century grew people’s feelings of nationalism. Jacob Grimm, one of the well-known brothers who wrote “Grimm’s Fairy Tales,” was influenced by the rising nationalism and devoted himself to researching the common roots of the Germanic people. Back then the Germans were divided into many duchies and counties, and the German language was the obvious element that united them.

Grimm compared words from different languages with the same meaning, for example, The Latin “pater” and the English “father.” He identified repetitive patterns of sound changes between words. For example, the words pater and father sound the same, except the sound “P” became “F” in English. This change, known as a “sound shift,” occurred in many other words, which allowed Grimm to further identify several shifts such as the shifts from “T” to “D”, from “C” to “H” and more. These sound shifts were named after him – they are called “Grimm’s Law”. This sort of “linguistic law” allowed linguists to identify several other sound shifts in different languages.

The discoveries within the Indo-European language allowed linguists to do the impossible (well, what had seemed impossible) – they reconstructed more than fifteen hundred words, even though they had no written evidence of the language . They did it by comparing words from different languages with the same meaning, and reverse-engineering them. In other words, where a “P” became “F” – they reversed the sound: from “F” back to “P.” If after the process of reverse–engineering, different words of different languages became the same exact word – then it makes sense to assume that this is how the original word sounded in the Indo-European language, the mother of all modern variations.

Jacob Grimm’s work with reverse-engineered words revealed a never-before-seen glimpse into the lives of the mysterious Indo-European culture.

“There was a process by which linguists looked at the words and then compared that to archeological evidence and other known historical accounts. And they tried to piece it together – and what they found is that the pieces do fit together if you look very closely.”

Where Did They Live?

So let’s look closely, as Kevin suggests. What does what we’ve learned about the Indo-European language reveal regarding the lifestyle and culture of the Indo-Europeans?

The first question is, where did they live? the descendants of the language were really spread out geographically: from the north pole in Norway and Sweden all the way to the humid valleys of Central India. Did the Indo-Europeans live in Europe and then migrate south, or move from south to north?

“There were words within the language for cows and sheep and horses, but there were no words for exotic animals. No words for animals from the Arctic, no words for animals from the Mediterranean. The same thing for plants: birch trees, elm trees – a lot of plants you’ll find in moderate climates, but no words for plants you’d find in the Mediterranean or further south.”

Let’s look further. Using their language, we can also define the eastern border of where the Indo-Europeans lived.

“They had words for Honey Bee, and Mead and Honey. And honey bees only lived in certain parts of Europe: basically in the area west of the Urals. So as you put all those pieces together, you can narrow the scope to a certain region.”

The archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests that the Indo-Europeans lived, most likely, in the wilderness north of the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, in an area that is today’s Ukraine and southern Russia – the same wilderness that later became the home of the Mongols where Genghis Khan had his great conquering spree.

When Did They Live?

Words we now know in the Indo-European language – such as weaving and sewing – reveal when the people of this culture lived.

“They have references to weaving and sewing – and that implies that there were sheep that had wool that was long enough for that purpose. Archaeologists know that European sheep didn’t have wool long enough when they were introduced. They have a sense of when sheep were introduced, and how long did it take for the wool to grow. So, these random pieces of knowledge get thrown into the pot.”

Words that describe wagons and riding horses suggest a lower boundary for the Indo-European timeline – since until forty-five hundred BC, approximately, things like wagons weren’t invented yet. And we can put the upper boundary of dating when they lived at the point when the Indo-European language started splitting into other languages known to us today.

“Beyond that point, we start to see the emergence of the first daughter languages, the first branches of this family start to become distinct. The Hittite language in Anatolia is generally considered to be an Indo-European language, and it’s in existence around 2000 BC. The Mycenaean Greek language, it’s in place around 1700-1800 BC. Sanskrit pops up shortly after that. They know that by that point the ancient language started to fracture to the various daughter languages that came later.”

All these calculations put the culture of the Indo-Europeans between roughly forty-five hundred BC and twenty-five hundred BC–about a 7000-year span. It is important to note that these are estimates, of course, and that not all experts agree on the details and assumptions – yet this is the general consensus.

Life in the Bronze Age

What else can we learn from the reconstructed words of the Indo-Europeans? Well, the words sheep, calf, cow, and ox suggest that they had domesticated animals that they used for work and food. They also had dogs: the word “kwon” is the Proto-Indo-European word for “dog” , and the source for the word “canine.” They also had words for a plow, furrow, and flour mill, so we know they had agriculture skills.

They lived in structures called “domo” – a word that came over to English as “domestic.” Overall, the Indo-Europeans had more words for animals – domesticated and not – than for plants or agricultural crops. This fact suggests that they relied on hunters and shepherds rather than on farmers and agriculture.

The Indo-European language also reveals clues about the social structure of its people. They had more words to describe male relatives than female ones. For example: “napot” – is a word that describes any male relative who is not a son. By the way, this is the source for the English word nephew and the term “nepotism” as a sort of having influence due to family relations. The abundance of terms for describing males within a family, in comparison to fewer words that describe female relations, suggests that the Indo-European culture was patriarchal.

From one unique word we learn another fascinating characteristic regarding social aspects of this culture – the word “ghosti.” In modern English, like in many other languages, the words “host” and “guest” are two separate words, with two different, distinct meanings. A “host” is someone who invites people to their home, while a “guest” is the one visiting. These two words both come from one word, the Indo-European “ghosti” – where the sound “G” shifted to “H” – which means that “ghosti” holds a double meaning: both guest and host!

The fact that “ghosti” has a double meaning tells us that in a nomad society where migrating tribes often crossed into each other’s territories, today’s guest can be tomorrow’s host. This assumption leads us to believe that hospitality was significant to this culture. The word “ghosti” is the source for other modern words such as “hospital”, and “hotel” – both involving a meaning of hospitality. In addition to the positive side of hospitality, the word “ghosti” is the source of the word “hostile” which means that guests are not necessarily friendly. I’ve been told that the modern Russian word for ‘Host’ actually still preserves this double meaning, and Russian is also a descendant of the Proto-Indo-European language. Anyway, These were just a few examples of what is believed today about the Indo-European people.

A Mystery

So the linguistic evidence indicates that Indo-Europeans lived about six thousand years ago in the Eurasian Steppe, but they weren’t the only people around, you know. Europe had already been settled by farmers who made their way to the continent from the Middle-East. In Mesopotamia, urban civilizations were getting ready to become some of the greatest empires human history had ever known – from Sumer to Assyria.

But this raises an interesting question: What enabled the Indo-European language to spread over continents at the expense of other languages? A first clue to solving the mystery can be found, of course, within the Indo-European language itself!

“There’s a lot of mystery here, but there are clues in the language. The references to certain technologies: wagons, wheels, they have lots of words related to horses and horse riding. So we know they were herders, nomads. They didn’t build cities and stay fixed in one place.”

The Indo-European had advanced technologies for their time. The word “ekwos” means horse, the source of the modern word “equestrian”. Well, riding horses and being able to harness them was pretty advanced in the early Bronze Era, and existing European natives didn’t have those skills yet. Having horses and carriages meant the Indo-Europeans could move around a lot, free of constantly being dependent on water and food sources– they could travel far distances. This was a big advantage over other people without those skills.

There isn’t much archaeological evidence from the early era of human history. Most of what we know about the people who lived in Europe and in the Eurasia Steppe regions back in the Bronze Age comes from graves known as the Kurgan Burials. These graves are one of the few known remnants that belonged to an ancient culture – the Yamna People. The Yamnas lived in the Eurasian Steppe around forty-five hundred BC, and many scholars believed they were the Proto-Indo-Europeans, that is – the people who spoke the Indo-European language. But since the Yamnas were nomads, and the only evidence of their existence are a few dozen graves, experts couldn’t prove the connection.

DNA & The Yamna People

But thirty years ago, a new revolutionary technology gave scientists a powerful tool for dating ancient remnants: the molecular clock. The molecular clock allows scientists to identify and trace certain DNA mutations across generations, and map the ancestry of entire populations.

In 2015, geneticists from Harvard University published a research study where they analyzed more than a hundred skeletons found in Europe and in the Eurasia Steppe – most of them from the Kurgan Burials. The result of the research pointed out, with strong probability, that around twenty-five hundred BC the Yamnas left the Eurasia Steppes, stormed into northern and central Europe and spread their DNA among the local population. The genetic findings, along with the linguistic evidence, strengthen the theory that the Yamna people were the Indo-Europeans.

The genetic discoveries also offer an answer to the question we asked earlier: why did the Indo-European language spread so far and wide, relative to the other languages which existed at the same time?

Well, The Indo-European language has quite a few words related to milk and other dairy products, and we know that its people raised domesticated animals like cows and sheep. This suggests that dairy was a significant part of the Yamnas’ nutrition, even though the ability to digest dairy isn’t so obvious.

“Today many people are tolerant to Lactose, but if we go back to this period – almost everybody was intolerant to Lactose. You couldn’t have digested milk and cheese beyond children. Genetics discovered that within this same region, among the same people, there was an evolution that allowed them to become Lactose tolerant in adulthood.

It is believed that this was a contributing factor because now they didn’t have to kill animals for meat – they could live off the milk and dairy. They also believe that this allowed them to become bigger and larger. These people had particular burial sites called ‘Kurgan Burials’. [The archaeologists] noticed that people buried in those graves are several inches taller than other people. They were living a healthier lifestyle. They had a healthy diet.

They were expanding into areas where people were hunter-gatherers. It didn’t take much of an advantage for them to overwhelm the people they encountered during that time.”

So, this means that the Yamnas – the speakers of the young Proto-Indo-European language – had a mutation that made them able to digest dairy even as adults–which was rare at the time. This sort of nutrition made them stronger, and along with the advantage of riding horses and not having to depend on water sources, this meant no one could stand in their way. They conquered enormous territories and replaced populations less advanced and weaker than them. This is how the path was paved for the Indo-European language to spread all around Europe in the west, India and Persia in the east – and later, even farther.

“Then you have to consider that through colonialism and expansion those languages have continued [to spread]. You can view the colonization of north and South America as a later Indo-European expansion. English, French, Spanish, Portuguese – those languages are now the dominant languages in the Americas. You end up with about half the population of the world speaking Indo-European […] We might not be done with this expansion – it may be still ongoing.”

So, if we measure “success” in terms of spreading your language and culture –the Yamna People might be one of the most successful groups in human history.

But there seems to be one group of people who resisted the Yamnas and their impressive horses and milk-fed muscles.

“Where they hit their limit is when they hit Mesopotamia and the near-east [who had cities.] It is believed that this is why the languages stopped at the point. In those areas, you have a different language family – the Semitic language family. Once there was a civilization in place, the advantages they might have had in Europe and Northern-India were kind of limited.”

Indo-European and the Semitic Languages

The fact that the walls of the great cities of the Euphrates and the Tigris – Iraq and Syria of today – blocked the Yamnas and the Indo-European language from spreading, made me think of an interesting question: My mother tongue, Hebrew, belongs to the family of Semitic languages – which are very different from English, French, Spanish, and other Indo-European languages. Still, could there be a connection between the Semitic languages and the Indo-European ones? In other words, could there have been an even earlier culture that spoke a language that later split into the Indo-European and the Semitics languages? I asked Kevin that question, and it turns out that I am not the first to think of it.

“This is a question I get asked quite often. At this point, there isn’t really anything definitive, but we know that languages don’t appear out of nowhere – they evolve over time. They come from somewhere. There’s a general agreement that there was an older language that preceded the Indo-European language.

Another expert in this field is John McWhorter, who wrote several books about the history of English. Scholars noticed that there are a lot of words in the Germanic languages that don’t come from Indo-European, such as ‘sheep’. John Mcwhorter argues that these words may have come from a Semitic language. He thinks that during the time the Phoenicians were expanding around the Mediterranean, maybe a group of speakers migrated into Europe and settled in northern Europe. He claims that he identified links between these words and Semitic words. It’s his view and it’s not generally accepted in the linguistic community, but he is very much on the cutting edge. I’m fascinated to see where this research goes because it could show that a core of the Germanic languages might have a Semitic root if we look close enough.”

Less Like Total Strangers

This episode reminded me of something. Do you ever get that feeling of estrangement when you travel abroad? When you don’t speak the local language, and no one speaks English? But revealing connections between languages that until now seemed so foreign and complicated, changed the way I think of languages. Farsi, Latin, and Sanskrit always seemed odd in comparison to English, French, or Spanish – languages that we’re exposed to almost on a daily basis. Knowing that there is one source for all these languages – a unique and very old language- makes it easier to recognize the similarities and resemblances.

So maybe next time we walk the streets of Mumbai or Tehran, or the next time you get sick in Thailand – we won’t feel like total strangers…

Ran Levi is a Science & Technology author, and the co-host of Curious Minds Podcast. Read More.