Written By: Ran Levi

In the 19th century, two brave (and some might say – insanely brave) French physicians took to the streets of Hong Kong and Bombay and risked their own lives in the name of ridding Mankind – and the fleas – from their worst nightmare: The Black Death. This is their story and the story of the humankind’s bitter enemy throughout the ages: the Bubonic Plague.

This Article is available in Audio as a Podcast. Subscribe to access the MP3 file: iTunes | Android App | RSS link | Facebook | Twitter

Explore episodes in other categories:

Astronomy & Space | Biology & Genetics | History | Information Technology | Medicine & Physiology | Physics | Technology

The Black Death Comes To Europe

In the middle of the 14th century, rumors of a terrible disaster in India and the Far East started spreading around Europe. Some people said that a horrible disease wiped out everyone in India…Others heard tales of showers of fire and burning rock destroying entire cities. Reality finally caught up with the rumors in 1347.

Merchant ships from the Far East anchored in Italian ports and dispersed some very sick sailors. They had big swollen masses on their necks, underarms, and groins; they had high fevers, were vomiting and had diarrhea. In some cases, their skin turned a purple-black color and their flesh and body fluids smelled really bad. Within a week, most of these sailors were dead, but not before spreading their sickness to the cities where they’d landed.

From Italy and the Balkans, the mysterious Plague spread all across Europe. Out of every five people who caught the disease, four were dead within days. This was, without a doubt, one of the most traumatic periods in human history. Yet it was not the first, nor the last, of it’s kind.

Ideal Conditions For An Epidemic

The three hundred years before the 14th century were comfortable, weather-wise: the average temperature in Europe was about 1 degree higher than it is today. A single degree change doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it had a big effect: many glaciers retreated north, uncovering new ground that could be cultivated. New land to farm meant more food, and prosperity, and a bigger population.

But by the beginning of the 14th century, the party was over. The temperature cooled back down, and was becoming even colder than normal: it was the beginning of what is known as “the small ice age”, which went on until the middle of the 19th century. As the temperatures dropped, fields were covered with ice and snow, and there was a lot less food to go around. Thousands of people died in the famine that followed.

So when the mysterious disease brought from the far east spread around Europe in the late 14th century, where hunger and poverty were already rampant –it was the ideal conditions for the outbreak of an epidemic.

The Plague Hits

No one knows for sure where the plague came from, but the leading theory is that it started in China, and traveled to Europe on the heels of the Mongol invaders of the 13th century. According to some reports, when the Mongol army in 1347 besieged the city of Caffa in the Crimean Peninsula, the Mongols catapulted infected corpses over the city walls. This caused foreign traders to flee the city – and some of them, already sick with the plague – or the Black Death, as it was known – brought the disease with them to Italy. From there, it spread quickly. And wherever it went – people died. A lot of people.

In Paris, which had a population of about a hundred thousand people in those days, eight hundred people died each day. That’s one percent of the population dying every day, and overall, it wiped out half the inhabitants of the city. During the Black Death, England’s population decreased from seven million people to only two million. It’s hard for us to grasp these numbers. It’s as if 200 million people died in the U.S. alone, in four years.

Death Is Everywhere

Try to imagine what the people of the time must have been thinking and feeling. Piles of bodies were stacked up in every village and every town. The stench of death was everywhere.

Here’s a quote from an Italian named Angelo di Tura, who survived the Black Death:

“They died by the hundreds, both day and night, and all were thrown in those ditches and covered with earth. And as soon as those ditches were filled, more were dug. I, Angelo di Tura, buried my five children with my own hands.”

In the English town of Durham, a church attendance record states that –

“No tenant came from [the town of] West Thickley because they are all dead.”

A monk in Ireland wrote:

“It was very rare for just one person to die in a house. Usually, husband, wife, children and servants all went the same way, the way of death. And I, Brother John Clyn, have written in this book the notable events which befell in my time.”

John wrote a few more lines, and then the narrative breaks off. A different writer later added –

“Here, it seems, the author died.”

Society Crumbles

The social structure of the Middle Ages crumbled as the epidemic swept across Europe, and everyone was afraid of catching the disease. The great writer Boccaccio wrote that,

“One citizen avoided another…relatives never or hardly ever visited each other. …brother abandoned brother…and very often the wife her husband. What is even worse and nearly incredible is that fathers and mothers refused to see and tend their children, as if they had not been theirs.”

Boccaccio also said that many of the victims:

“Ate lunch with their friends, and dinner with their ancestors in paradise.”

Those who could afford it fled to secluded castles and isolated farms. The poor people in the cities had nowhere to go, and the worst of all – for them, anyway – there was no peace in their death. Most priests refused to come to the houses of the deceased, afraid of catching the disease themselves.

For the devout Christians, that meant losing their only chance to get to heaven after their death, and most of them were terrified of their fate. Under the pressure of the people, the church sometimes allowed even secular people to listen to last confessions on deathbeds, and if there wasn’t a man around – even a woman could do it.

The Plague of Justinian

The Black Death was not the first occurrence of the plague: in fact, it’s highly likely that this particular disease was a constant threat to humans even in biblical times. Every now and then it broke out in various cities in the ancient world, and it always came suddenly, as if out of thin air. People would start dying in a particular neighborhood, usually near the city’s harbor – and then the plague would spread rapidly inside the city – and then to neighboring cities.

The first well-recorded occurrence of the plague was in the middle of the 6th century. Today, it’s known as The Plague of Justinian, named after Justinian I, who was the emperor of the Byzantine Empire when the plague hit. According to sources of that era, the plague started somewhere in North Africa. It then spread to Egypt and from there to Constantinople, which was the capital of the Byzantine Empire and a major trading port.

The Plague and the fall of the Byzantine Empire

The plague hit Constantinople extremely hard: 50 million people died in a few years – that was a considerable portion of the population. A historian called Procopius who lived at that time writes:

“At that time it was not easy to see anyone in Byzantium out of doors; all those who were in health sat at home either tending to the sick or mourning the dead. If one did manage to see a man actually going out, he would be burying one of the dead. All work slackened; craftsmen abandoned all their crafts and every task which any man had in hand. […] People of all ages were struck down indiscriminately, but the heaviest toll was among the young and vigorous and especially among the men…”

This account hints at the devastating effect the plague had on the economic and military strength of the empire. The high mortality rate caused a severe shortage of labor: there were no farmers to tend to the fields, and so the plague was followed by a series of famines which hit the population even harder. Another writer tells of the impact of the plague on the empire’s army:

“The Roman armies had not, in fact, remained at the desired level attained by the earlier Emperors – but had dwindled to a fraction of what they had been, and were no longer adequate to the requirements of a vast empire.”

Many historians now believe that The Plague of Justinian had a lasting effect on the health and stability of the Byzantine Empire. The empire did go on to exist and claimed more and more land – but it never achieved the far-reaching glory that Justinian the First had hoped for.

The Black Death& The Church

And the Black Death of the 14th century–which was around 800 years after the Plague of Justinian–may have played a similar – or even a greater role – in determining the course of human history. In fact, we can still feel its influence today.

The institution that was hit the hardest by the plague was the Catholic Church. In those times, the 14th Century, the Catholic Church was really corrupt. The priests and cardinals weren’t ashamed to openly seek earthly delights: they wore expensive clothes bought with donation money, committed adultery, had illegal children, and to top it all – they sold indulgences. What that meant is that the pope and the cardinals granted, for a price, an official letter to confirm that God – or rather, God’s representatives on Earth – forgave the buyer for their sins and that the Pearly Gates were once again open to them. An indulgence was basically buying your way back into heaven. It didn’t matter what horrible crime you committed: murder, treason, theft of any kind – if you were rich and bought an indulgence, the church forgave you. The church’s image was very weakened by this corruption…And then came the Black Death.

Monks died, just like everyone else. Priests died – just like everyone else. Cardinals – those who didn’t flee to their secluded resorts – died, just like everyone else. The public believed that God had grown tired of the immorality of the church, and the torrent of death God had rained upon humanity didn’t favor the good Catholics over the bad ones.

Extreme Forms Of Repentance

Some people developed a deeply cynical attitude towards the church, God, and life itself. This state of mind was evident in a common artistic motif called “Danse Macabre” – or “Dance of Death”. These were paintings that depicted the angel of death as a demon or a skeleton holding a trident, leading a procession of dancing skeletons from all classes: priests, nobles, beautiful maidens, and simple peasants. The stylized paintings convey the idea that death makes no exceptions.

The belief that God was punishing humanity for its sins lead some to extreme forms of repentance. A particularly fascinating sub-phenomenon was the rise of self-flagellation groups. Members of these groups, which flourished in the apocalyptic atmosphere of the Black Death, tried to convince God to forgive humanity by imitating Jesus’ torture. They would go from town to town in processions of hundreds, chanting hymns and flogging their own bodies with whips and sticks. When they reached a certain verse they would fall to the ground and crawl, even if at that moment they were walking over sharp rocks, thistles or open sewage. Big crowds gathered wherever these processions passed, encouraging the sufferers, feeding them and giving them gifts.

You might think that the Catholic Church would appreciate the sacrifice and torment of the flagellants, but it was the opposite. These groups were a direct threat to the status of the Church because they declared that they – and not the corrupt Church – would save all of the humanity from destruction. The public stopped making donations to priests and monks because these flagellation groups were the ones who appeared to make a real, selfless effort to please God…The Vatican reacted quickly and violently to this threat: the Pope issued urgent letters, declaring the flagellants as heretics and enemies of “true” Christianity. Many of them were imprisoned or executed. That was more or less the end of self-flagellation groups.

Economic And Social Effects

The Black Death also had an interesting economic and social effect. In Western Europe, where the epidemic hit the hardest, there was a serious lack of people to work the farms. Overall, about 25 million Europeans died in the Black Death – about half of the entire population. As a result, the demand for farmers grew and landowners were willing to pay higher wages and provide better living conditions. The balance of power began to turn: the peasants now had more choice and more control of their future – and so the aristocracy started to lose its power.

The Authorities struggled to stop this and even passed laws that forbade the peasants to leave their masters or demand more payment. But it didn’t work…this shift in the balance of power weakened the church and the aristocracy, and it meant the rise of the middle class as a powerful part of society. Those who lost faith in the infinite power and wisdom of the Catholic Church started coming up with their own ideas about freedom and faith, which eventually led to the ideas of the Renaissance.

But even when the Black Death finally ended – the plague didn’t go away.

“Bad Air”

It most definitely didn’t. Over the next few centuries, the plague erupted in almost every major European and east-Asian city, from Milan in 1629 to London in 1665 and Marseilles in 1720. Millions of people died. And no one knew why. No one knew what caused the disease, how it spread so quickly across continents…and of course, doctors in the Middle Ages were pretty much powerless to do anything about the epidemic.

The popular opinion was that the plague spread through “bad air”. The solution was to disperse the bad air using incense or to place a handkerchief soaked in floral extract over the mouth. Some physicians tried making ointments and blends out of exotic plants, rare metals, and powder from crushed gemstones. Some people believed loud noises would drive death away, and in some cities, big church bells clanged constantly. Charms, spells, and magic of any kind was tested, but of course, they didn’t help.

Here’s a curious anecdote. Shortly after the outbreak of the Black Death, Philip the sixth, King of France, asked the medical faculty at the University of Paris for their opinion on the cause of the disease. The physicians considered the question, analyzed the symptoms, examined the evidence closely and eventually arrived at the conclusion that a triangular joining of Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars in the Aquarius constellation was responsible for the disaster…With modern knowledge, of course, we can now point to the real culprit: a bacterium called Yersinia Pestis.

The Plague hits Hong Kong

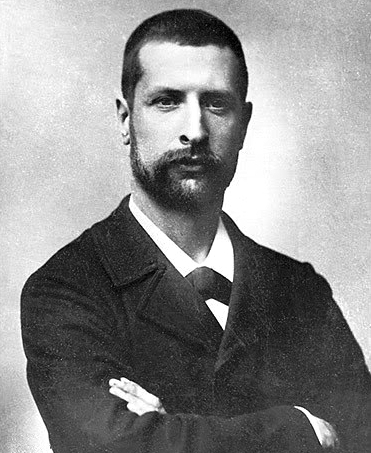

It was discovered simultaneously by two physicians in 1894: The french Alexandre Yersin, and the Japanese Kitasato Shibasaburo.

in 1894 the same plague hit Hong Kong. It was known as the ‘Bubonic Plague’ by then, after the distinctive swollen areas that appear on the patient’s groin and armpits, which are called buboes. The authorities asked for assistance, and the Japanese physician Kitasato soon arrived from Tokyo. Kitasato was a distinguished scientist, who already had success in discovering and isolating a different type of harmful bacteria. Kitasato set to work in Hong Kong and did some post-mortem autopsies on people who died from the plague. He identified the bacteria responsible for it – but his examination wasn’t conclusive, and he still had some doubts.

Meanwhile, just 3 days after Kitasato, a young french physician named Alexandre Yersin was sent to Hong Kong by the Pasteur Institute to do his own research. Since he was late to the party, he found that all the cadavers in the morgue were reserved for Kitasato, and the authorities didn’t want to let him near them…so all he could do was work with live patients who were sick with the disease – which wasn’t what he wanted.

Yersin Has Enough

So after 5 days, Yersin had enough. He found two English sailors who were assisting in the morgue – and bribed them to let him in. Once in the morgue, he managed to draw samples from recently deceased victims of the plague – and with these samples, he isolated the specific bacteria that was the probable cause. To prove this, he injected the same bacteria into mice and guinea pigs – who then died of the same plague.

Voila! Kitasato published his research a few days before Yersin, but since his results were inconclusive – Yersin got the honor of discovering the plague-causing bacteria first – and it was named after him: Yersinia Pestis.

We now know that once in the body, Yersinia Pestis attacks the immune system and proliferates inside lymph nodes – and from there, spreads to other internal organs. There are actually three distinct types of plagues caused by Yersinia Pestis, according to the way the bacteria spreads through the body: bubonic plague in lymph nodes, septicemic plague in blood vessels and pneumonic plague in lungs. In all cases, death occurs in almost 3 out of every 4 infections.

A Groundbreaking Experiment

But although the cause of the plague was now known – it was still unclear how it managed to spread so quickly. Some physicians thought the bacteria spread by contact with human waste, or absorbed by inhalation, or maybe by skin contact. It was another french physician, Paul-Louis Simond, who solved that riddle.

In 1897 Simond, who was also a member of the Pasteur Institute, traveled to India to replace Alexandre Yersin in the field. While working in Bombay, Simond noticed that many plague patients had, at the early stages of the disease, a small blister containing fluid and plague bacteria. This made Simond suspect that maybe an insect bite was somehow involved. At first, he considered cockroaches, but then he turned his attention on rats. So, he captured some rats and inspected them for fleas. That was quite brave of him, considering he thought those fleas might cause the plague!

In his hotel in Karachi, Simond conducted a groundbreaking experiment. He found a sick rat infected with fleas and kept it in a closed cage. He goes on to describe his experiment:

“After 24 hours the animal I was experimenting on rolled up into a little ball, with its hair standing on end; it seemed to be in agony. I then introduced into the cage a perfectly healthy young Alexandria rat caught several weeks before and kept sequestered from any danger of infection.

The next morning the sick rat had died without having moved from where it had been the day before. I left its body in the cage for one more day. During the next four days, the other Alexandria rat remained imprisoned and continued to eat normally. About the fifth day, it seemed to have difficulty moving. By the evening of the sixth day, it was dead.

An autopsy of the (previously uninfected rat) revealed buboes… The kidney and liver were swollen and congested. There were abundant plague bacilli in the organs and blood. That day, 2 June 1898, I felt an emotion that was inexpressible in the face of the thought that I had uncovered a secret that had tortured man since the appearance of plague in the world. “

How The Plague Spread

Simond’s hypothesis – that the plague spreads via fleas on rats – explains much of what we know about the plague’s behavior over the centuries.

Sanitation wasn’t a big thing in the Middle Ages. In many cities, people used to open a window and empty their chamber pots into the street. As you can imagine, rats thrived in the filth of Medieval cities – and furthermore, cats were considered to be Satan’s companions and were extensively eradicated, so rats enjoyed a carefree life. Rats also thrived in the close quarters of ships, and the maritime trade between Asia and Europe brought the plague to almost every major city.

Now, We should point out that fleas also suffer quite a bit from the bacteria. Yersinia pestis blocks the flea’s digestive system, so the flea is constantly hungry. The flea then bites its victims over and over again, trying in vain to feed – and in the process, injecting the bacteria into the wound. Eventually, the flea itself dies of hunger. So it’s fair to say that human beings are not the only one suffering from Yersinia Pestis: it’s also the flea’s worst nightmare, and the rat’s.

The Plague In Modern Times

The plague still exists, and every now and again erupts in developing countries – but thankfully, with modern antibiotics, treatment for the plague is effective, and the mortality rate is much lower. According to the World Health Organization, in 2013 there were 783 reported cases of the plague worldwide – out of which 126 people died. That’s about 16%. Remember, the mortality rate in the medieval days was 70%.

That’s not to say that those in developed countries are completely safe from the dangers of the plague. During World War 2, the Japanese army and scientists conducted secret experiments on prisoners of war, to evaluate the effectiveness of Yersinia Pestis as a biological weapon. Some 3,000 POWs were killed, in some of the most horrific ways possible, as part of this research. The Japanese developed bombs which held live rats and fleas infected with the plague and dropped them on Chinese cities during the war. It’s impossible to say how many people died as a result of these experiments: some say hundreds, some say tens of thousands.

After the war, the US and the Soviet Union developed biological weapons. It is believed that in the height of the Cold War, both powers had major stockpiles of advanced strains of the plague – some that were resistant to antibiotics.

Let’s hope, for the sake of humanity, rats, and fleas, that the plague will remain locked away in the history books.